-

To

chevron_right

ICANN’s DNS Blocking Report Presents Three Key Recommendations

news.movim.eu / TorrentFreak • 9 June • 6 minutes

In 2006 alone, Russia-based AllOfMP3 reportedly banked $30 million from sales of an unauthorized music product for which the major labels received no payment.

In 2006 alone, Russia-based AllOfMP3 reportedly banked $30 million from sales of an unauthorized music product for which the major labels received no payment.

The unlikely stage for the industry’s response to global sales of cheap, unlicensed DRM-free music, was Denmark. Under pressure from industry group IFPI, ISP Tele2 blocked AllofMP3’s domain, an event that will soon celebrate its 20th anniversary.

While never likely to threaten the site’s overall traffic, the Danish block was at once symbolic and historic. Nineteen years later, Denmark has almost 2,800 domains on its current blocklist, a figure that’s easily eclipsed by the tens of thousands of domains and subdomains blocked globally every month, largely without report or fanfare.

ICANN Publishes DNS Blocking Report

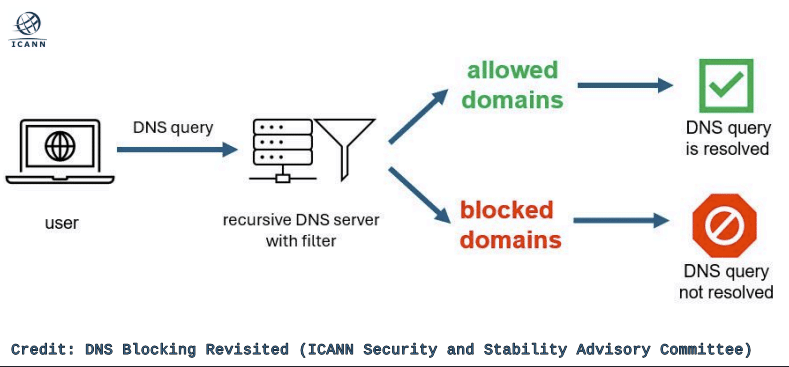

The Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers (ICANN) is the non-profit organization whose management of the internet’s name and number spaces (domains and DNS / IP addresses) helps to provide a stable internet. In a recently published report, ICANN provides a comprehensive view of the Domain Name System (DNS) and the effects of its antithesis: DNS blocking.

Published by ICANN’s Security and Stability Advisory Committee ( SSAC ), ‘DNS Blocking Revisited’ aims to raise awareness among all internet users, but especially those whose decisions can make a real difference. For those considering DNS blocking as a potential solution, to the authorities with the power to permit or deny its use, ICANN’s message is clear. Full comprehension of the potential repercussions of DNS blocking is a prerequisite to limiting harm.

“The aim of this report is to advise the Internet community, and especially policymakers and government officials, of the implications and consequences of using DNS blocking to control access to resources on the Internet,” the report begins.

“DNS blocking can have serious side effects. A block may affect users outside the jurisdiction of the party doing the blocking. Users may not know that a block is in place, and can interpret it as a site outage or other error, encouraging potentially insecure behavior to ‘fix’ it. A block may affect domains that provide services for other domains, causing collateral damage beyond the intended scope of the block.”

Motivation and Expectation

ICANN takes no position on whether DNS blocking is good or bad, or whether specific motivations to block tip the scales one way or another. Whether supported by local law, justified on morality grounds, or mandated by governments purely for the purpose of censorship, the report focuses on the technical aspects of DNS blocking, the consequences, and advice to limit harm.

The report defines DNS blocking as an approach to regulating or restricting access to information on the internet by interfering with the normal process of responding to DNS queries about domain names or IP addresses.

This is usually achieved by “denying that a name or address exists or by providing false information about it.”

While easy to implement, DNS blocking is only effective against users of the DNS where blocking is implemented, and has no effect on the existence of the targeted content, which remains accessible by alternative means.

These limitations should be well understood since they help to determine whether DNS blocking can fulfil the stated objectives. Having weighed the benefits and considered the implications, DNS blocking may not be needed at all.

“It is important that any entity mandating or implementing DNS blocking understands the implications of the technology. For example, DNS blocking in one jurisdiction can affect the accessibility of content in another jurisdiction. Legal authorities should form technically informed views about DNS blocking, and understand if, or the extent to which, DNS blocking may accomplish their goals and how it may affect parties outside their jurisdictions,” the report adds.

Bad DNS Blocking is Bad

DNS blocking often amounts to the protection of business interests, yet blocking for security reasons is encountered by millions of internet users every day. They include shielding minors from harmful or adult content, use of domain blocklists by major web browsers to warn users about unsafe sites, and DNS filtering to prevent exposure to malicious domains. An example cited by ICANN suggests that DNS blocking may even be a less restrictive alternative to avoid the global consequences of suspending an entire domain name.

Yet, regardless of motivation, DNS blocking measures of any kind should have clearly defined scope.

“While one jurisdiction may find that it is allowable and desirable to block a domain name, another jurisdiction may consider blocking that domain to be a violation of human or civil rights,” ICANN says.

The report highlights legal action by rightsholders against Quad9 and Cloudflare. Where DNS blocking by ISPs targets a specific, clearly defined local ‘audience’, DNS blocking at public resolvers used by a global audience risks overblocking on a much bigger scale.

In a case involving Quad9 , a court order to block specific sites on copyright grounds offered no guidance on key technical issues, leaving Quad9 to block the sites globally, to avoid being held in contempt.

DNS Blocking Weakens The Battle Against Security Threats

ICANN’s report highlights issues involving internet security that are either caused or exacerbated by DNS blocking measures. For example, redirects due to DNS blocking can cause browser TLS errors that ordinarily signal a potential security threat. ICANN suggests that over exposure effectively ‘trains’ users to ignore certificate mismatches.

In the wider fight against global threat actors, DNS block circumvention reduces visibility of both traffic patterns and security threats.

“DNS data gives Internet Service Providers (ISPs) an important and accurate picture of both traffic patterns and security threats on their networks,” ICANN reports, adding that DNS data can help ISPs diagnose denial-of-service attacks, identify infected hosts, compromised domains, and vulnerable customers.

“When users turn to alternative DNS servers, some network operators, ISPs, and enterprises may experience decreased ability to manage security threats and manage certain network operations. For example, if a user accesses the third party recursive resolver via an encrypted connection using DNS over HTTPS (DoH) or DNS over TLS (DoT) and is infected with malware, the user’s ISP may not be able to detect that and notify the infected user, since DNS telemetry is being diverted away from the ISP.”

Disclosure, Transparency, Blocking Infrastructure

While reduced visibility of threats is cited as a concern, the view of DNS blocking itself is often obscured by a lack of disclosure and limited transparency.

“[DNS] blocking policies and actions are often not disclosed to affected parties, including to end users. This can make it difficult for end-users to understand when they are being blocked, or why,” ICANN warns.

“Absent some level of transparency, DNS blocking can be difficult to recognize for what it is. It can be misdiagnosed as a hosting outage, a misconfiguration, or a malicious attack.”

Before concluding with ICANN’s recommendations, an issue touched on briefly in the report but worth highlighting again, concerns the construction and embedding of online infrastructure to facilitate blocking of piracy, fraud, ransomware, and botnets.

Citing a 2023 open letter written by TCP/IP co-developer Vinton Cerf, “Concerns Over DNS Blocking” warns that the same infrastructure could be easily adapted “to suppress internal dissent, censor outside information, and surveil dissidents and journalists.”

ICANN Recommendations

Listed here verbatim are three rock-solid recommendations from ICANN’s Security and Stability Advisory Committee.

Recommendation 1: SSAC recommends that any entity implementing or mandating DNS blocking understand the implications of the technology.

Recommendation 2: SSAC recommends that DNS blocking implemented by any entity — by a government or any organization that has policy, legal, or operational control over a network or service—follow these guidelines:

A. The entity should determine whether DNS blocking will fulfill its objectives.

B. The entity should have a clear policy about what and how it will block, with well-defined review and decision-making processes that minimize risk.

C. The entity should implement the policy using a technique that minimizes overblocking or collateral damage that could affect its users.

D. The entity should not affect networks or users outside its administrative control.

Recommendation 3: SSAC recommends that operators of recursive servers use DNS Extended Error codes (see section 6.6 Extended DNS Error) to indicate to end users and troubleshooters that DNS blocking is taking place

The report DNS Blocking Revisited is available here (pdf)

From: TF , for the latest news on copyright battles, piracy and more.

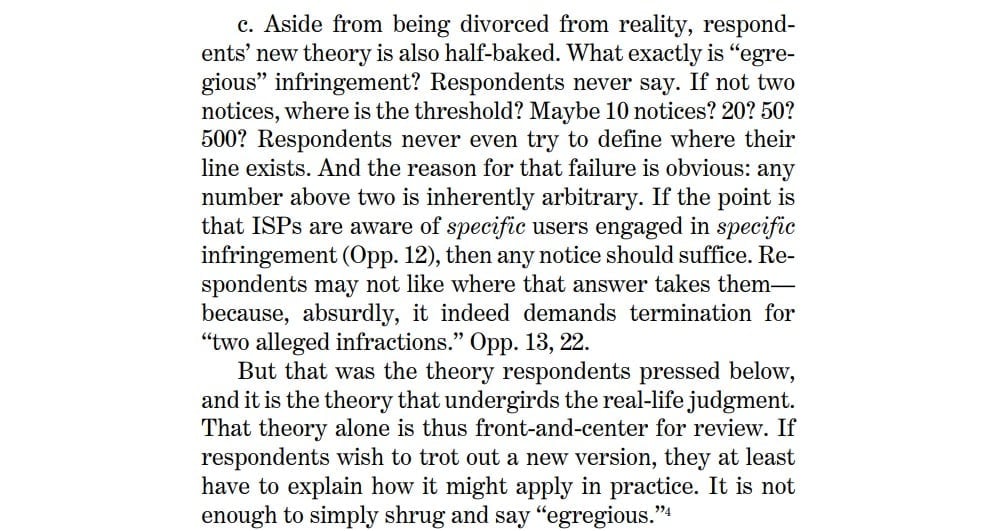

In late 2022, music industry giants including Warner Bros. and Sony Music secured a victory in their lawsuit against Internet provider Grande Communications.

In late 2022, music industry giants including Warner Bros. and Sony Music secured a victory in their lawsuit against Internet provider Grande Communications.

In common with many services provided by Google, its search engine is wide open and free of charge at the point of delivery.

In common with many services provided by Google, its search engine is wide open and free of charge at the point of delivery.

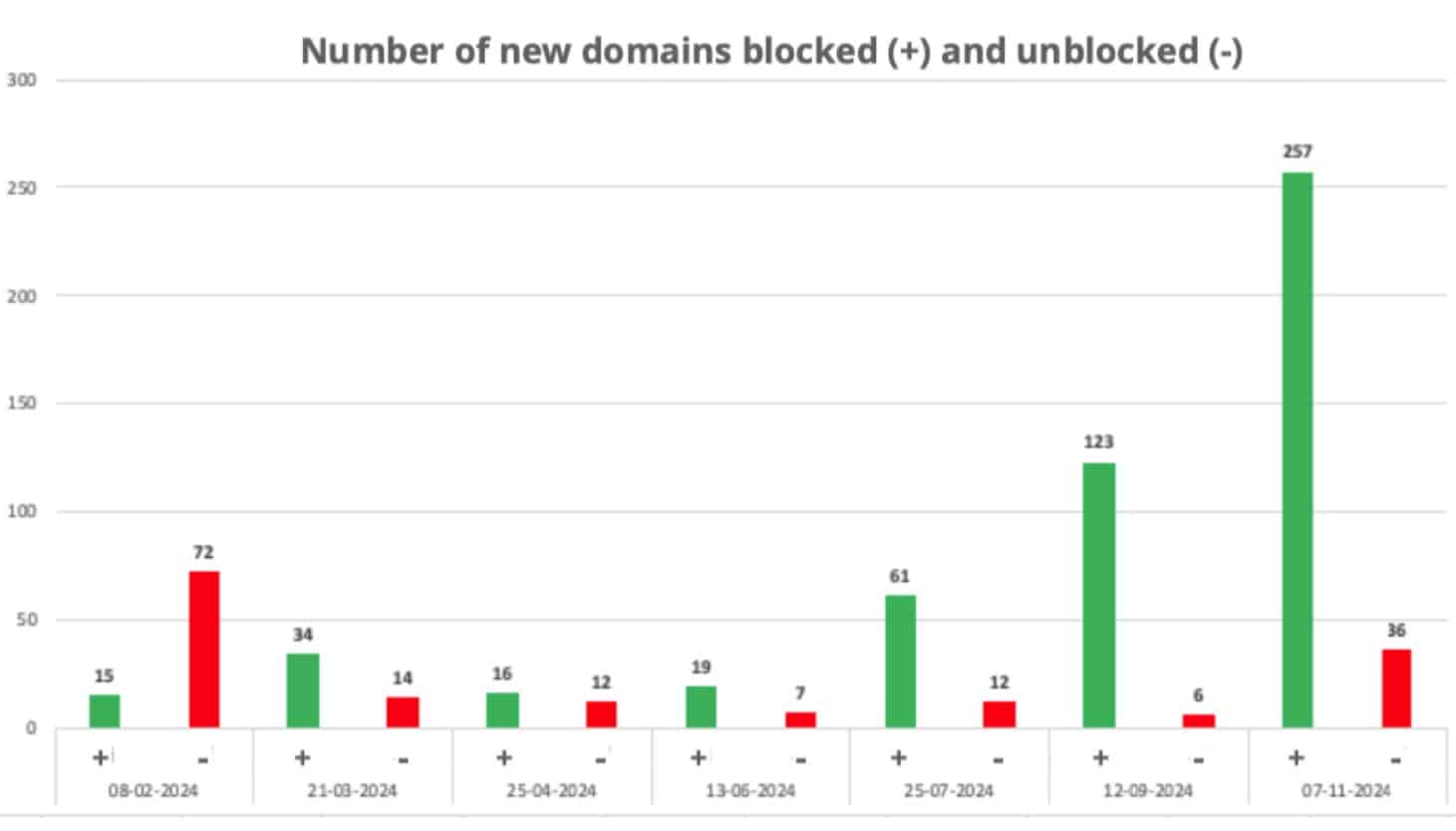

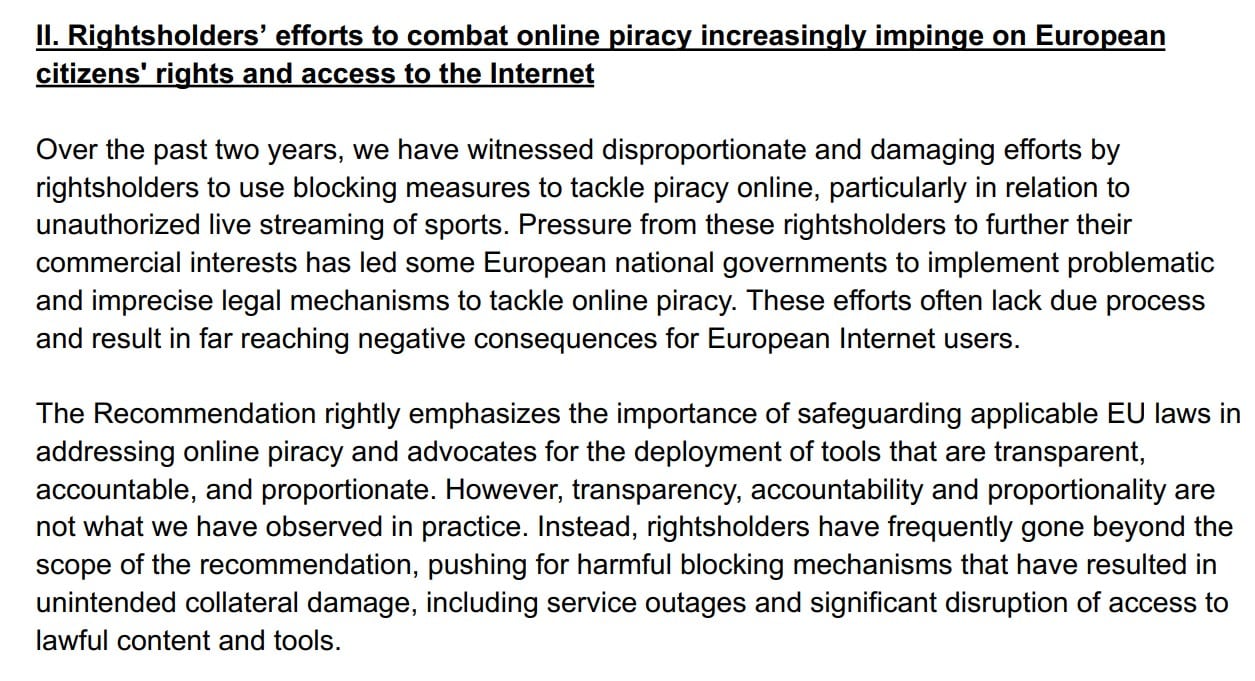

Two years ago, the European Commission published a non-binding recommendation to tackle the problem of live-streaming piracy, sports in particular.

Two years ago, the European Commission published a non-binding recommendation to tackle the problem of live-streaming piracy, sports in particular.

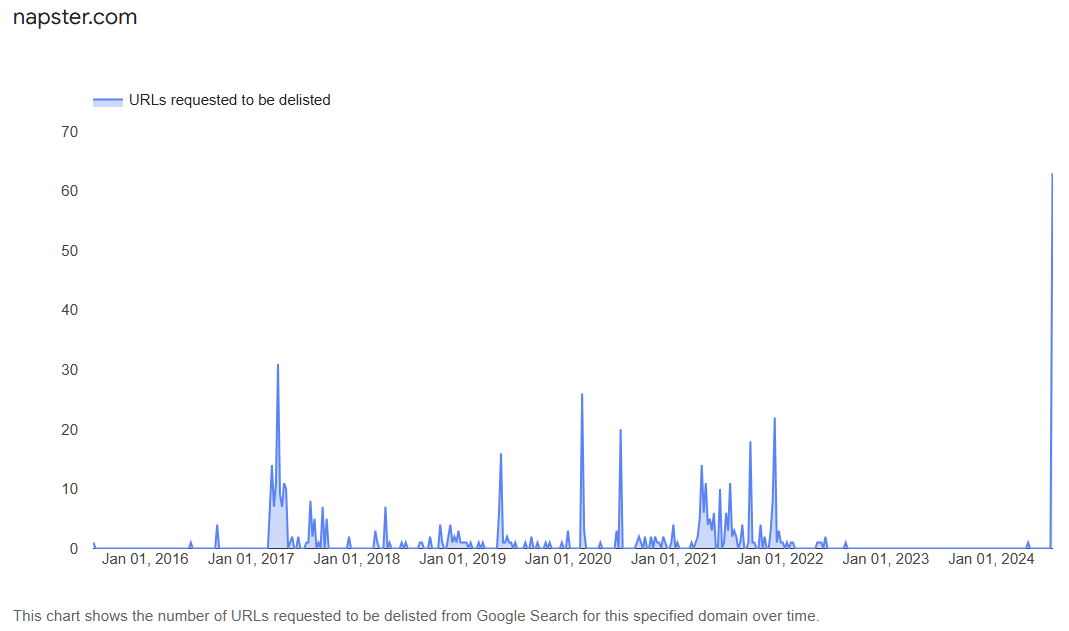

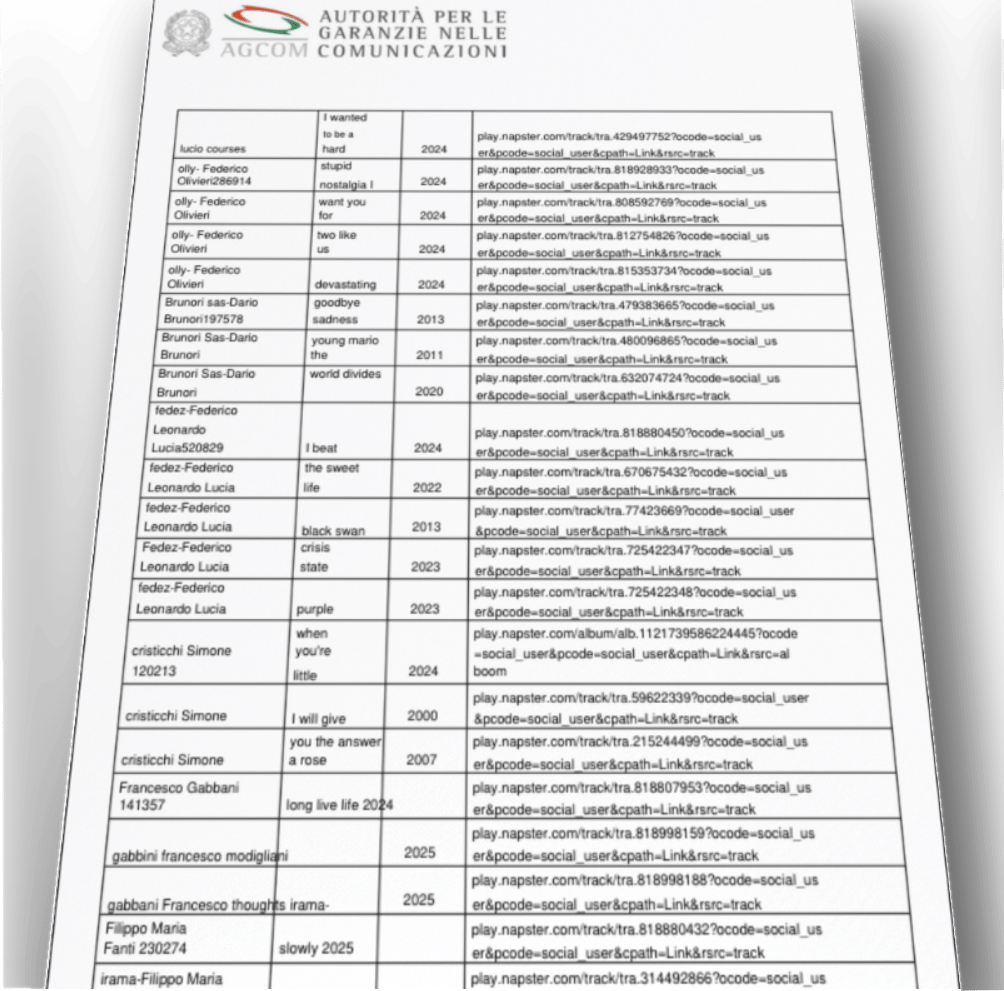

The original Napster service was launched by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker

The original Napster service was launched by Shawn Fanning and Sean Parker

After a decade of focusing efforts overseas, the push for website blocking has landed back on American shores.

After a decade of focusing efforts overseas, the push for website blocking has landed back on American shores.

In recent years, the European Commission has proposed and adopted various legislative changes to help combat online piracy.

In recent years, the European Commission has proposed and adopted various legislative changes to help combat online piracy.

BREIN has just published its latest annual report, providing insights into the priorities of the organization and the progress being made.

BREIN has just published its latest annual report, providing insights into the priorities of the organization and the progress being made.